The Alternative UK – for Ruptura Colectiva (RC)-

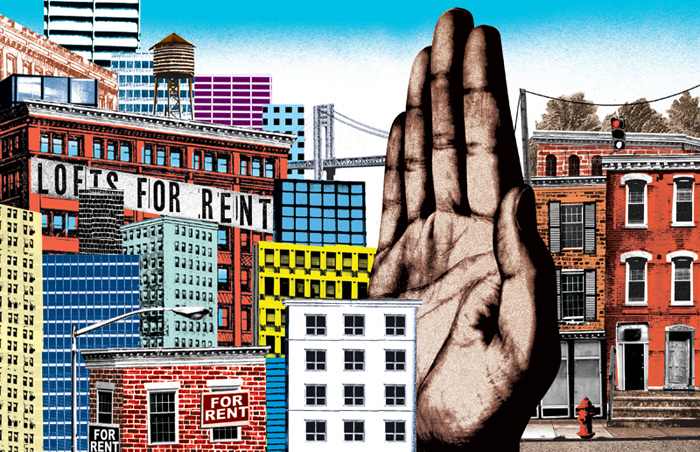

Gentrification – defined by Merriam Webster as “the process of renewal and rebuilding that accompanies the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas, often displacing poorer residents” – is a concept that people struggle over.

If it is about the super-affluent moving back into historic inner-city neighbourhoods from suburbia or beyond – pricing the locals out of their own property, or simply obliterating their buildings and erecting expensive new ones – then it’s easily condemned.

this week, concerning a Colombian-based indoors market in London threatened by developers, has been taken up no less than a UN working group on human rights and business. Professor Surya Deva of the group said:

“I think this is an issue which is not merely about developed cities – it is an issue which has global implications [over] the displacement of people from their properties and land… The problem can arise in a city like London or a remote part somewhere where there is a mining project…No country can claim that it has a perfect human rights record. When we receive these allegations we try our best to help.”

However, this story is more about developers (or “regenerators”) obliterating a rich urban texture that has built up over many years. What if the “gentrifiers” are ambitious young artists and bohemians, looking for old, cheap and unloved properties upon which to exert their energies? Sculptor Grayson Perry once called artists “the shock troops of gentrification” – trailblazers whose taste choices paved the way for property speculation.

But asked some honest questions about his own role in the potential “gentrification” of the Finnieston area of Glasgow, recent deemed “Britain’s hippest street” by the UK Sunday Times.

What if you’d come into the area looking for a place to make music, but had discovered that others just as precarious as yourself – food makers, pub owners, record shops – were also gathering round the sector? In short, are creatives to be damned for doing what they do – which is to create experiences and services?

Kane wondered if there were lessons in his story for how we sustain creative lives for the majority, not just for a hipster minority:

I guess my own dream is for “creatives” in towns and cities in Scotland to arise from a much wider social base than can be seen in London, New York or whereever. No tuition fees for students is certainly a start (and the return of grants could also help further).

But take the trendy policy idea of the day – universal basic income. Most plans for UBI rest on the following justifications – they’ll be paid for by higher-taxes on holders of extreme wealth; and they’re intended to cushion the disruptions of job-replacing technology.

But rarely is the argument made for UBI that it might provide a higher floor to support social and cultural flourishing. UBI could enable many more to live more bohemian, amateur and purpose-driven lives. Lives that are currently available to those with an accumulation of middle-class assets, whether financial, cultural or educational.

Shouldn’t it be our aspiration that more people pursue unalienated, self-fulfilling existences? It would be a real shame if we started to pile all the frustrations about our rotten work-life balance – or our poor distributions of wealth – on the frail shoulders of the demonised “hipster” or “creative”.

Note: A/UK friends might recognise this claim from – and his “” philosophy. It’s also worth noting that gentrification is now a planetary phenomenon – see the work of .

117 total views, 2 views today